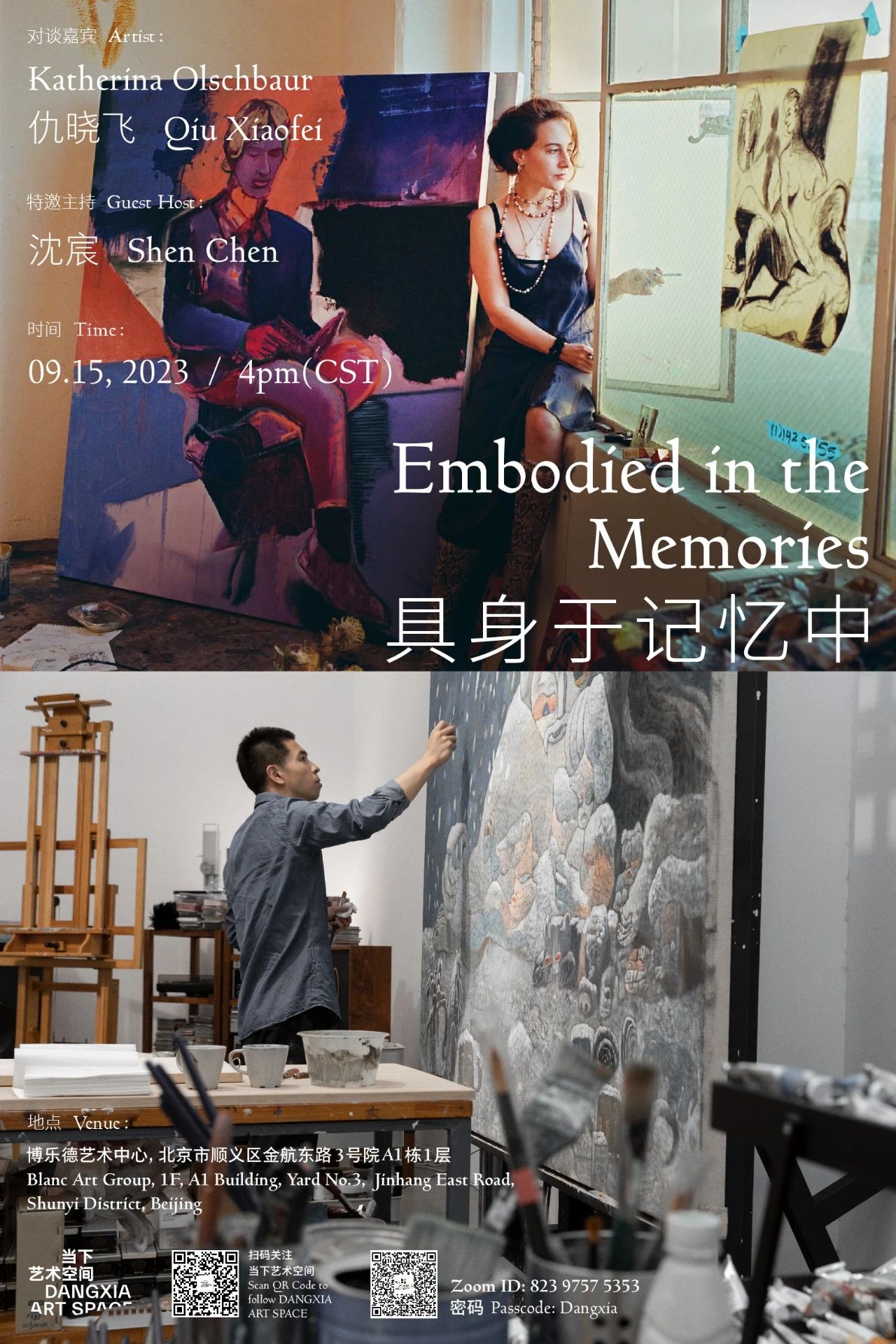

DANGXIA Talk: Qiu Xiaofei and Olschbaur on “Embodied in Memory”

“Painting is much bigger than us”

Shen Chen

Thanks to DANGXIA Art Space for your invitation. Kat and us visited Qiu Xiaofei’s studio very briefly, and that was the first time for all three of us to meet each other in person, so I am sure the conversation today is going to be fresh and spontaneous. The two artists come from really distinct backgrounds, one from the East and the other from the West. Kat was born in Austria and is now based in Los Angeles, United States, while Qiu Xiaofei is from and based in China. During my research into the artistic history of the two artists, I realised that there is a lot of similarities, such on the topics of individual memories, collective memories, cultural memories, and also the way they understand painting through embodiment, treating it as an embodied practice. My first question is for Kat: would you like to briefly introduce the exhibition “Sirens”, and what are the ideas behind the overall planning of the exhibition?

Katherina Olschbaur

Thank you for inviting me here to show my paintings and to talk about them, and thank you for coming to the space to see my paintings. This is a new series of paintings I’ve been working on for the last couple of months. The show is called “Sirens”. The sirens are figures from Greek mythology. They are actually in between women and birds, mostly appearing along a journey. They have a very distinct song and this song is supposed to be very seductive and very, very dangerous, luring the travelers sometimes into danger, sometimes into death. So yes, this was the starting point for my paintings.

Shen Chen

The next question is for both of you: if we look at the history of your art, it is clear that both of you went through the same kind of transformation: from a relatively figurative painting practice you moved to making abstract paintings, and then you both returned to a more figurative, representational gesture. I wonder how did this shift happen, and how do you see the relationship between figuration and abstraction, and does the change reflect a change of focus?

Qiu Xiaofei

I think the categorical distinction between abstraction and figuration comes from the viewing experience. If we consider it from the artist’s perspective, one may say that the foundation of all paintings is abstract. Artists create paintings using brush works, colours and forms. Different conceptual trajectories lead to different visual results. For me, it’s clear that experiencing painting is just like understanding time and experiencing life: it is a spiral movement in which one has to endlessly go back and forth before finally being able to move forward. It is likely that your painting may at different times manifest different routes and trajectories. When we want to destroy an image, then the final result may turn out to be abstract. When we want to compress ourselves, and return to a historical narrative, then the final result may end up being figurative and representational. I think an artistic development is not linear like a train track, but is rather like the track of a roller coaster — voluted and spiral. It spins indefinitely; at one point it presents figuration, at another it leads to results that are more open-ended.

Katherina Olschbaur

It’s very to the point. I agree. I also think that the relationship between abstraction and figuration, in my practice or in general, is not linear, is not one after the other. In a way, they give each other a hand, but not always peacefully. Often I need a narrative as a starting point, it’s almost just as a jumping board to jump into a painting, but then what holds the painting or what creates the substance, can only be achieved through abstraction. What is so interesting is that we both had these different phases where we also stepped into abstraction.

From my point of view, it was definitely a sense of crisis that I had in my more narrative works — that I was too close to the narratives. I felt this was not painting, so I gave them up. In about 10 years’ time I had to develop the formulation in abstraction, but then I also realized it was also not enough. So it is, for me, as if to be in both worlds, so to speak. There also is a need for complication, for complexity. Sometimes it really is a fight in between realities, but in the end, one holds the other, and one builds the ground for the other. Figuration is built on abstraction and abstraction is built on figuration. Or maybe not; I also agree that abstraction is the more fundamental experience of painting. The narrative is mostly something we interpret through our cultural background or narratives, but abstraction like the presence of the materiality, the presence of color, of light, of the flesh, so to speak — these are what transcend. I would also agree that abstraction is even the deeper base.

Shen Chen

Qiu Xiaofei, you mentioned temporality and the issue of destroying or destructing an image; In your practice, you’d sometimes appropriate photos and historical images, reconfiguring them in your paintings. What’s your take on photography and digital image? We are today living a world that is completely surrounded by digital, photographic images. What do you think is the relationship between photography and painting? Why deal with photography in your paintings?

Qiu Xiaofei

A common understanding of photography as a medium treats it as a reflection of history, of life and of reality. But as far as painting is concerned, a photographic image is definitely more profound than that. For example, it can represent a certain understanding of light. I was talking to Kat earlier about the different light sources in her paintings. In photography, which is an extension of Western painting, the light source is very unique and fixed; all the figures have to be covered by a same light. But I can see in Kat’s paintings that there are many light sources; there are self-luminous and backlighted objects. Some scenes are lit as classical paintings are, by a light source that is outside of the picture.

Therefore, although a painting may have referenced different images and established ways of rendering light, it as a whole could be appreciated as iconoclastic because it undoes the convention of using a singular, fixed light source.

Those who believe in the linear evolution of painting are caught in an embarrassing situation: it deems that there is less and less a painter can do, the path to breakthrough just gets indefinitely narrower. But if we don’t think of the history of painting as an evolution, we can go back to, say, Egypt, where the very ancient Egyptian art is naturally not concerned with the invention of photographic representation. An examination of Egyptian art tells us that all images are generated in a structure that is surficial, flat and narrative. The simple point is that, as far as painting is concerned, one can go beyond the confining understanding of it, an understanding that accumulates in the time between the beginning of the Renaissance and now. I think all painters practicing today are interested in this project: take image as a starting point, before trying to break away from it, getting rid of the conceptual and artistic restrictions it imposes on us; locate historical references and supports, and then combine contemporary and historical experiences, and even archaic experiences from the realm of deep time. This is my answer to Shen Chen’s question regarding departing from figuration: I think it’s a natural development that goes with a deepened understanding of painting, the world and art history.

Katherina Olschbaur

I also agree with the point that painting is in a way not connected to photography… They has a more complicated relationship. I think it is the aspect of time, that differentiates them both. I always found it very difficult to translate. For example, photography is into painting directly because photography happens mostly in one space. And the time is very, very defined, so you know exactly at what time it happened. There are definitely special forms of photography, especially when there is surrealist play with materiality and exposure in nonlinear ways. But mostly, I think the aspect of time adds and creates more depth in painting.

Painting is more related to time-based media than to photography, but we live in a time that is so defined by photography, so we can’t avoid but have to deal with that, especially also because we often see paintings through the lens of photography, because we often encounter a painting for the first time on a screen. There is a dominance of a photographic gaze that kind of limits things or flatten things down. But painting always has much more dimensions. I think, in a way, contemporary painting has to definitely break these structures down, and create their own sense of time.

Shen Chen

You just talked about the use of light source and the issue of temporality in painting. In Kat’s paintings we often see clearly defined, manifest light sources. Sometimes the light comes from within the painting, sometimes it come from multiple sources and in a very surreal way. But in Qiu Xiaofei’s case, the existence of light source is not that obvious. The presence of light is often murkier, stickier and subtler. I wonder how do both of you render light in your paintings?

Qiu Xiaofei

In painting, the significance of light is much more than a visual effect. When we were in my studio yesterday, we talked about the use of ochre, a very bright, mineral yellow colour in painting. The materiality of the mineral pigment is to this day irreplaceable. The origin of that painting of mine was an experiment with ochre I did on raw, unprimed canvas. I realised that, simply by applying ochre along with its material energy on canvas, you may render light. The part of the canvas that was covered with ochre became particularly bright, and in contrast, the rest of it turned somehow purple for human eyes. I will then have to think about what kind of image may be related to this material energy and this effect of light, such as what experiences of mine can be associated with this visual effect at hand? In the painting, and in my understanding it has to do with witchcraft and alchemy — what appears to be light in a painting comes with a lot of implications.

Katherina Olschbaur

Light or painting itself is occult, is a form of alchemy. And I agree that light, most of all, has a symbolic meaning and it’s also about power. So when I start to think about a painting, light is very, very crucial in the process. There is a certain hierarchy within a painting that is defined by a light source, which is supposed to be in the center. But I was always interested in all the forces that oppose that, like I was always interested in the shadow areas. So when I start to paint a painting, I will have a ground line for a light, but then I’m giving all my attention to the shadow and all the colors that I see in opposition to the light source.

In the end, I create all these kind of rebellious narratives, so to say, that counter the initial hierarchy of the center, or of the light. So there’s so many side stories happening, so many little light sources that create new narratives or distract your attention in a way. So in a sense, it is building up a certain dynamic that always counteracts something like the central light source.

Shen Chen

Light in relation to temporality goes beyond simple concepts such as day and night of course. I feel that there is ambiguity of time in your paintings, where you gather different times and pertain to different temporalities in very complex ways. For example, you appropriate childhood memories; you depict historical images from archives; you summarise immediate experiences, etc. It is clear to me that time is complex in your painting practice, and you are not only interested in depicting the morning sunlight or the shadow of the night.

Qiu Xiaofei

Temporality in painting… The light at 12 o’clock today may be very close to the light at 12 on a certain day in one of your memories. It is not necessarily linear. A painting reminds you of a moment in time many years ago; at that moment, the two times are closer together, closer than the distance between “today’s noon” and “this morning”.

I think the magic of painting forms a wormhole, or rather, it is a VR world that one person enters first. The painter opens a world through his memory, his recognition of energy and his self; the person who sees the painting, if he can enter the world of painting, he enters a spiritual realm. I think this may be the unique charm of painting.

Today, painting has another important meaning for me: we all want to gain a kind of freedom, which in reality is confined within the narrative of history or the linear logic of time. Everyone gets old; everyone dies; the world is moving unequivocally towards a technological end, etc. Linearity brings us too many problems. Therefore, for me, painting is a kind of relief, freeing us from such a regimented, disciplined mindset.

Katherina Olschbaur

I have read that you talked about how painting creates this kind of space where one in the present time can touch history. Maybe it’s my interpretation, but you said something in that sense that I really can relate to. This is very interesting: if you look at the lifetime of a human, it is a very short window of time. But we, in painting, can really talk about times that are really far behind, or before, or they also can be times after, so painting extends the lifetime of a person. Nevertheless — and this is based on everything that I heard — when we are coming towards the end of the lives, we tend to go backwards. We will think about our childhood also.

I also have to say that in terms of light, I sometimes think of very, very basic experiences that I had when I was two or three. We internally can touch these experiences even if we talk about something now. So for me, sometimes there are different thoughts about temporality that plays a role, because in my work, it is almost like a conversation between different forms of speed. Something happens in a very erratic way, and this erratic energy, then I have to balance out, or have to challenge through not making a decision for weeks. I like to extend certain ideas of time, in a way like going to some kind of…Something that I can’t extend longer. This is why for me, physical sensations of tiredness or awakeness, they are tied to day-to-day experiences. They are important and I use them in a way. So there’s a way of thinking that I can do in the morning and there’s a way of thinking I can do in the night. So for me, the day-to-day is actually very important, but then of course we have to bring this into a much bigger context. A painting is bigger than our own existence.

Shen Chen

Both of you have talked about painting as a temporal being that constantly jumps around from one point to another. I have also observed that there is some constant repetition or return of figurative gestures or motifs in your work. According to my observation, there are two different types of this process: one is the repetition and return over a relatively long period of time, such as the boats and the seascapes in Kat’s “Transformation” series from 2006 to 2008, and then, more than ten years later, we can still see the presence of the sea and boats in the exhibition of “Sirens” On the other hand, Qiu Xiaofei’s open arms, forests, and Eastern Orthodox church architectures continue to return in your paintings. The second type is: in Kat’s work for example, the image of a woman lying on her side or on the ground recurs frequently.

My question is: is this a conscious process, or is it more spontaneous? Being carried out at different stages, do such repetition and return assume the same role and significance?

Katherina Olschbaur

As an artist, it’s sometimes difficult to say if it’s not but only looking backward. I would say, especially if it’s objects or motifs that appear at an early stage and then they come back, I feel I need to have 10 years passed before I can understand it. But definitely, I think it is maybe subconscious, but it only creates meaning if it becomes conscious, or if it can be really used. But I also think that in the end, if you look backwards, we don’t have so many themes. We only have a handful, maybe five or less, even maybe just one.

About the motif of the lying figure — I don’t know, I think it really has to do with gravity but also with emotions of feeling heavy, but also of interest in elements that go upwards, very light elements, this is just something that holds us down. Gravity is what we want to overcome in a society, but in the end, we are tied down.

Qiu Xiaofei

If we look back at history, we will actually realise that good painters spend their entire lives painting one painting or several paintings, because existence is well recognised as finite and limited, and this understanding enables us to reach infinite possibilities. It’s been 20 years since I graduated from The Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA), and I’m actually an artist who has changed a lot. I have explored various fields, styles and ways. There are probably a few things that have remained the same. Let’s take two examples: the image of the house has always appeared in my paintings — from the earliest images drawn from my own memories and experiences, such as the house I used to live in when I was a child, to today’s kind of anthropomorphic or more abstracted houses, etc. Let’s also consider why the house is an important subject for painting. This is because, when a painter paints a house, he is dealing with two spaces at the same time, one space is external and the other is internal. Our understanding of these concepts is constantly renewed as we live on. What is external and what is internal? Regarding the medium and the object, our understanding of life evolves. Although there are many paintings of houses, in the course of twenty years, the meaning of the paintings has advanced far beyond my understanding of the concept of the house itself.

The human figure is another theme that many painters have been dealing with. After I have experienced aging and death, after I have personally experienced the physical demise of a human being, my understanding of the physical, anatomical human body and limbs is completely different. So, although we seem to be painting the same image, the same painting, the same subject over and over again, we have actually infused in it our daily experience or all our understanding of life. A good painter spends his whole life exploring a very limited number of themes.

Shen Chen

So Kat mentioned the concept of gravity and materiality, while Qiu Xiaofei talked about the concept of space or spatiality. Regarding gravity, I think both of you have a flowing, fluid quality in your paintings, but the process of realizing this quality is not quite the same; Kat’s paintings often involve imagery of water or the ocean, but the figure is in a very fluid, even turbulent relationship with the ocean and the water. The figures seem to be floating on a violent water surface, and at the same time, because they are usually at the edge of the whole picture, they seem to be pulled or tied down all the time.

The melting texture in Qiu’s work can be seen in paintings such as Red: the figures look like they have been set on fire, slowly melting down like candles, and at once extending and spreading out like plants. You mentioned spatiality earlier: many of Kat’s works spread out along the side of the picture, leaving the center of the picture a void or a source of light, etc. In Qiu’s paintings, on the other hand, the human figures often occupy a relatively central position. The two approaches bring about very different senses of space on a psychological level. One medium through which a painting is realised is your own body in action, so I’m interested in this question: working on a composition, where do you usually start from, and how do you slowly construct the space of the painting through your actions and movements?

Katherina Olschbaur

It’s very interesting; I just thought about it that yesterday we haven’t talked much about it, but I think a lot about Austrian art, this is my cultural background — Actionism, in particular. So it’s about very intensely challenging our own psychological states and also our own body, which is something I also grapple with. I want to go further, and don’t want to be completely tied down just by, say, physical sensations, but they do definitely also play a strong role. I also think a lot about Maria Lassnig, who consciously dealt the sensations of the body as the border between between the inside and the outside. So these things definitely play a big role, but not always harmoniously. So, how I build a painting is: I go through stages of a lot of imbalance, and through the act of painting, and through finding certain areas and grounding it down. It’s a highly physical way of crafting.

And also, as I mentioned earlier, different psychological states are important for me, like tiredness or excitement. So they definitely play a role, but I also try to look in a very rational way at a painting. This is also maybe my criticism of Austrian art, which is always about destruction, self-destruction, expressivity. Even if I use expressive marks, I don’t actually think my work is…I wouldn’t describe my work as expressive, because it’s also in a way very, very critical of it.

Qiu Xiaofei

I think this has to do with personal experience. You mentioned fluidity and stickiness earlier, didn’t you? This stickiness — I wouldn’t think of it in that light myself, it may be a critic’s word. But for me, certain changes and developments that are perceived by the audience may take place, because people’s life perceptions vary. In the past, I might understand people in terms of their identity: for example, a father is a father and a child is a child. But when I really came into contact with the birth of a child, or the death of an old person, after I really came into contact with their bodies, my understanding of the biological, physical attributes of human beings changed. So some of the objects and images in the paintings may reveal changes that you see, such as a kind of stickiness or a kind of biological form.

An example I’d like to raise here is: we had adopted some cats 20 years ago. Many years passed, and they died. After they died, we found a cemetery in Daxing district, Beijing and buried them in it, putting up a tombstone. Later, due to the construction of an airport there, the cemetery could no longer be used for pets. In the end, the result of the negotiation was that the bodies didn’t need to be moved, but it was necessary to bury them under a thicker layer of soil, and we could still come and visit, but you couldn’t practically see anything. I have since gone back to visit the cats, and the soil just covers everything; but you are informed that your cats are buried right here. The feeling I get now when I look at that ground is different from the feeling I got in my heart years ago when I went and saw the tombstone as an object. This is just one small example; when the image of the land reappears in my paintings, I bring such an experience into it, which may be why the paintings have that stickiness you mentioned.

Shen Chen

Talking about the spiritual or mystical experience of painting, and the relationship between painting and alchemy that Kat has just mentioned, I noticed that in the previous two years, both Qiu Xiaofei and Kat have mentioned the concept of divination in their respective solo exhibitions: Kat’s exhibition in 2022 is entitled “Prayers, Divinations“, and Qiu Xiaofei’s exhibition is straightforwardly titled “Divination“. Of course, the original narratives and contexts of the exhibitions are different: Qiu Xiaofei’s “Divination” is inspired by the story of Qu Yuan’s divination in the ancient classic Chu Ci, while Kat’s “Prayers, Divinations” responds more to religious texts. But both exhibitions touch very explicitly on the influence of traditional culture, art history, and classic texts on your work. I think there was also a strong sense of spirituality in these exhibitions, about how we should face ourselves spiritually in the present. Kat raised a direct question: “How can I capture the spirit of another person?” The story that Qiu Xiaofei quoted pointed both potentially and directly to the principles of how one should act in times of chaos.

I would like to ask: in your creative process, how does the experience of spirituality connect with painting through the physicality of the body? And if there is indeed a correlation between your work and the mystical narrative of divination, I’d love to hear your thoughts on that connection as well.

Qiu Xiaofei

For me, mystical experience is a very complex and contradictory spiritual experience. There is an old Chinese saying that goes: “one shall not speak of strange powers and pagan gods”; for us, mystical experience has always been related to witchcraft, that is to say, it is in a different system. For me, however, this mystical energy does move painting forward, and also allows the energy of painting to penetrate the possibility of understanding the world. The contradiction between these two spiritual pursuits has always been present in my work.

Two years ago, I used the concept of “Divination” for my exhibition in New York. As you all know, The story of “Buju” or “Divination” is one of the articles in “Chu Ci“: Qu Yuan went to the high priest and asked him what should we do when the world is so miserable? The high priest put down his turtle shell and divination tools and said: “I can’t solve your problem, you should return to your heart and ask yourself what you really think.” This story I quoted at that time is very much in line with my contradictory state. Therefore, in my paintings there are two elements present at the same time: the element of supernatural strangeness exists of course, but the more important element is permanence. For example, I paint a lot of mountains, which are transformed into the image of a motherly, matriarchal entity, whose eyes are made of the sun and the moon. It is a kind of embrace gesture. In this state, everything in the picture, whether it is death or new life, is embraced in a permanent state, which was the starting point of the exhibition at that time. So I used the word “divination” for the title of the exhibition.

Katherina Olschbaur

I also believe in witchcraft of course — I do, in life and also in painting. But it’s interesting because Western culture always had a very bad time with witchcraft since it seemed too dangerous. In the Western world, men should be on top of things and everything else should be controlled. So it does not have a really good standing within Western culture. In the exhibition that took place two years ago, I tried to see painting as prayer or to put myself, in a way, below. But also in this exhibition I was showing a lot of portraits. I was equating the act of painting, of being able to paint another person, of being allowed to paint another person as a spiritual act: it does not involve imposing yourself on top of them, and does not involve you being under them, but you have to dedicate your whole attention almost as if you pray towards person you are painting.

So it was about to paint them in that sense, but their spirit has to be somehow above you. I equated the act of painting another person as a spiritual act, or it has to be a spiritual intention, rather than depicting a person in order to objectify them.

Shen Chen

I am going to raise my last two questions together. I’m not a painter myself, so I am always curious: as creators, what are you looking at when you look at other people’s paintings? When you say that a painting is a good painting — we may look at the classic paintings and say that it is a good painting, or we may look at contemporary paintings and point out that it is a good painting — are the criteria for the different statements the same? What defines a good painting?

Another question is: what is the biggest artistic challenge you have encountered so far?

Katherina Olschbaur

I don’t know, I think I am a very impulsive person, so sometimes I walk through and see something and I really hate it. My instinct is mostly like that. I don’t like something, then I give it another look, and then I can be really overwhelmed by something, in a positive way. I don’t know, it’s difficult to say.

Qiu Xiaofei

I agree with what Kat just said: painters are not above paintings, because paintings choose and shape people, and the world of painting is much, much bigger than an individual. What is a good painting? The definition is constantly changing in my understanding, just like my understanding of people, existential crises, and solutions are constantly changing.

Facing the world of painting is facing the world of life, and I don’t see any difference between the two. I also feel that what painting gives me is far more than what I give to painting. The process of understanding painting differently at each stage is actually the process through which it feeds me: for example, it has allowed me to find paths to solve spiritual and existential crises. This is, in my opinion, the relationship between a painter and painting. It’s nothing like the usual ideas like: I’m an artist, I create everything, I’m quite an empty concept — it’s not like that at all. I even feel that the relationship between the artist and the painting is like playing Tai Chi: he hits back and you hit over, and I keep losing to him, but there are times when I feel like I have got the upper hand and I can be happy, right?

Katherina Olschbaur

Yeah, that’s very well put. I also agree that maybe the painting actually knows more than we do, and it depends on our receptiveness. There are some paintings that don’t really speak to us, and it’s good to just leave it, don’t engage with them any longer. But there are some paintings we need to come back to. So I find it very interesting to come back to a certain work after a period. I have this often with other artists: they don’t talk, I don’t react, but in a specific moment in my life, suddenly I feel the whole world opens up by me looking deeper on the life of a certain artist that is no longer there.

The other question about the challenge, It is complicated, because I think on the one hand, the biggest challenge is maybe us standing in our own way, but also another challenge is to be misunderstood, that people don’t understand the work. But then on the other hand, I feel a lot of works only can be understood backwards. Some works are not being fully understood at the time they are made. So there is this very interesting dynamics between being understood and not being understood — being misunderstood and boxed in. There’s a certain challenge that lies within ourselves and then there’s a certain challenge that lies within the world we are born into, and the ability to understand painting. We live in a very fast world, very unfocused…not unfocused, but there are a lot of focuses spread out on very different places. Painting requires a certain concentration. This is definitely a challenge, but I think it’s also worthy tackling this challenge.